According to the latest Nescafe advert, we’ll meet nearly 80,000 people in our lifetime. But how many will really make an impact on us? Abdou Diallo certainly has on me. At our first meeting at the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) Congress in Orlando in summer 2016, I could tell, just from our initial conversation, that he is a passionate patient advocate in the haemophilia community. However, it wasn’t until a chance acquaintance in Amsterdam two weeks ago that I found out just how remarkable, poignant and inspiring his story is. I was so moved that I wanted to use this blog to share what living with severe haemophilia has meant for him and why he’s so encouraged to help others.

Younger years: ‘A time of struggle’

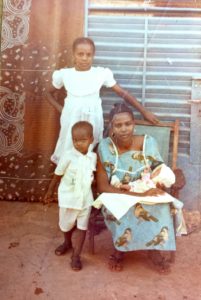

He began by telling me that growing up in Burkina Faso, West Africa, in his own words was, “A long, solitary journey.” Haemophilia wasn’t understood and people would ask, “What is this kind of new disease?” In Abdou’s culture, there was an expectation for him to be circumcised in order to ‘become a man’ but he couldn’t; Abdou has painful memories of one of his two cousins who died because of this. His mother felt responsible and guilty for Abdou and his little brother’s inheritance of the condition and for the fact that his sister is a carrier and passed haemophilia to her son. Abdou did stress that the bond, in particular with his brother, has been strengthened by their shared understanding and experiences of everyday life with a bleeding disorder, calling themselves true ‘Blood Brothers.’

Living in the capital, Abdou was based close enough to the hospital to receive whole blood transfusions if he had a serious bleed, however there were no clotting factor concentrates available. This blood was mainly donated by his father or aunt, as it could take two weeks to get a match from the blood bank. Abdou explained that it takes large volumes of whole blood to stop a bleed and it wasn’t always possible for his father to provide sufficient amounts, due to his age and own health. Therefore, in an emergency, sometimes his father’s friends would donate, too. I asked if he ever felt at risk of blood contamination but he replied, “It was based on trust… I’ve been lucky to not contract any infections.”

Abdou has developed three target joints; his right ankle, left knee and right elbow. When he had a bleed, he would either stay in bed for two or three weeks with nothing to do but, “Let the pain do its dirty job on [his] body,” or be admitted to hospital; his longest stay lasting three months. I was shocked and horrified to hear that when Abdou was 15, the doctors suggested amputating his leg in order to, “…avoid the continuous bleeds and reduce the burden of hospitalisation”. Abdou was so scared that, from that day, he refused to ever go back.

Abdou leaving home: ‘I wanted to follow my dream’

At 19, determined to study engineering, Abdou secured a scholarship and moved to Morocco. Was it a risk to relocate to a country also with no access to clotting factor? “No,” he said, “It was as much of a risk to stay… the opportunity to learn and study was priceless.” His flatmate there was a friend from high school and he helped Abdou a lot when he couldn’t work. As he said, “He would bring me food and if I couldn’t use my two elbows to put the spoon in my mouth, sometimes he would feed me like a baby.” By now, there were fresh frozen plasma transfusions available but even still, he was tired of waiting for it to be effective, explaining, “I was seeking a drug that could prevent me from bleeding.”

Finding the answers: ‘I knew that going to France would save me’

With sheer resilience and a ‘warrior-like’ attitude, Abdou wanted to prove to himself that, despite everything, he could be the best in his studies and, “…be at the top one day!” The opportunity to do a PHD in Normandy also offered a potential solution to accessing clotting factor, which Abdou had heard of: “It was kind of a dream… the long-awaited drug that would change my life.” After arriving first in Caen, he had an initial observation by a local haematologist, who didn’t believe he had haemophilia, even though he had his old papers from Burkina Faso. Abdou has always made a point of strengthening his muscles after a bleed, mainly through walking. Seeing him myself, I for one couldn’t have guessed the extent of what he had gone through. However, a blood test did confirm what he knew already: factor VIII deficient below 1%.

Sunday 4th December 2011 is a day he’ll never forget. At 24-years-old, he was to receive his first ever clotting factor. He recalls, “I saw the factor coming and my tears just came down.”

Fate takes a turn: ‘I was the unluckiest person in the world’

Abdou had to wait four to six months for full health cover and the permission to start prophylaxis. During this period, he would have another bleed in his knee. He soon realised the treatment he had so longed for wasn’t working: “My doctor tested me for an inhibitor and I got the bad news.” They proposed to start immune tolerance induction (ITI) to try to eliminate the inhibitor but this process can be really intensive, as very high doses may need to be used more often and it’s not always successful. Abdou explained, “I was changing and trying to find my way… I wasn’t ready to start this.” He still lives with an inhibitor and has gone onto ITI as well as treating with a bypassing agent.

Sense of togetherness: ‘I used to believe we were alone on the planet’

By chance, through a work project, he came across the French Haemophilia Society on Google and saw they were hosting a congress in Paris that year. He asked for a meeting with Thomas Sannié, now President of the organisation, which surprisingly would be his first contact with another haemophiliac. He recounted, “We went to a café and I told him, ‘You are the first guy outside of my family with haemophilia I’ve met, let me touch you…’” Sharing his journey, Abdou felt an immediate connection and sensed Thomas was saying to him, “I know you, I know your pain and I know it’s terrible but I’m with you.” He has been volunteering in France ever since, as well as working for Unicef in Paris.

The bigger picture: ‘We are lucky men’

There’s mounting excitement around new haemophilia therapies and gene therapy becoming a real prospect. But like Abdou asked, “How can we accept extending the inequality gap… to get some new, crazy treatment whilst letting other people continue living without?” His background is still being replicated in many areas of the world where there isn’t access to safe and sustainable clotting factor. I totally endorse Abdou’s sentiment that it’s our responsibility, where developed healthcare systems exist, to campaign and raise awareness for all those who aren’t on an equal footing. As Abdou says, “The WFH is doing a lot of things for treatment for all… but we can’t let them alone do that, it is our duty, too!”

On behalf of On The Pulse, I would really like to thank Abdou for making this possible and encouraging us to become activated for our fellow ‘Blood Brothers’ where treatment is not always an option. If you have a question for Abdou or would like to make any comments, tweet me and the team at @PulseInSync or send an email to [email protected].

Take care,

Laurence

(Editor’s note: Featured image showing [L-R] Abdou, Jose Jimenez and On The Pulse’s Laurence Woollard in Amsterdam, October 2017. Thank you to Madz Smethurst – Twitter @MaddyBubs – for copyediting support.)