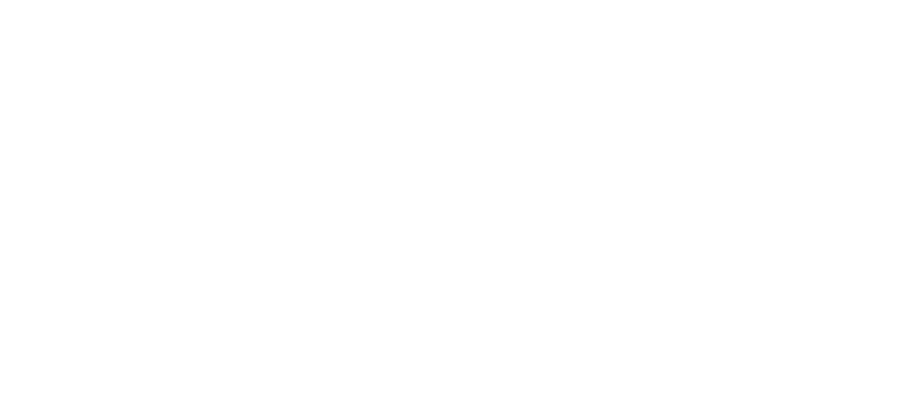

This month’s guest for our Factor This! blog series needs no introduction. Mark Skinner’s universal reputation as a stalwart advocate and progressive leader for people with bleeding disorders very much precedes him.

Mark’s wealth of experience spanning over 30 years, makes his CV read like a How to book for specialising in international public policy and healthcare development. Having previously held senior positions in trade associations and state government, Mark’s own lived experience of haemophilia would lead him to serve as President of both the National Hemophilia Foundation (NHF) in the U.S., and World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH).

He’s since gone onto head up global outcomes-based research initiatives in haemophilia, to build a robust evidence base for patient decision-making. Mark was also recently appointed as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence and Impact at McMaster University, and continues to provide global health strategy consulting through his company, Institute for Policy Advancement Ltd.

We sat down with Mark to reflect on the legacy he’s creating in haemophilia, and his viewpoints on treatment access and ongoing innovation from a personal and global context…

1) Mark, to begin with, please could you share some of your early experiences of haemophilia?

![]() I was born in 1960 at a time when clotting factor concentrates didn’t exist. In fact, cryoprecipitate hadn’t yet been discovered.[i]

I was born in 1960 at a time when clotting factor concentrates didn’t exist. In fact, cryoprecipitate hadn’t yet been discovered.[i]

By the time I was in the second grade, I was wearing a brace on my leg and using a wheelchair. I have to give a lot of credit to my parents for their extraordinary resilience back then. My older brother has haemophilia, too.

They had that fine balance between wanting to hover, protect and help us avoid the pain of a bleed. But also realising boys will be boys and, ‘you’ve got to let them take risks.’ We wouldn’t have made it through that period without them!

2) Did your family have a positive influence on your career?

![]() They were always very socially conscious and politically involved. Because of them, it helped me appreciate that there was a big world out there, beyond what I just knew growing up in Kansas.

They were always very socially conscious and politically involved. Because of them, it helped me appreciate that there was a big world out there, beyond what I just knew growing up in Kansas.

I was intellectually curious. I’d thought about going into the foreign service or international development. But it didn’t seem right with my haemophilia.

My parents, whether they realised it or not, were very good at channelling me to pick other interests. I needed to rethink my priorities, even more so when I found out about living with HIV.

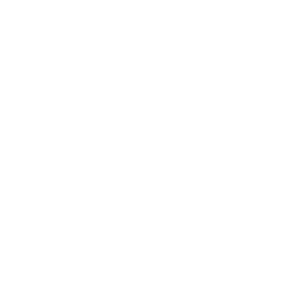

3) By 1982, HIV had been identified in the haemophilia community. Could you briefly describe how your life was at this time?

![]() It was the same year that I graduated from university. There was already some pre-knowledge of what was going on. It wouldn’t be until I finished Law school in ’85 that I learnt of my own HIV diagnosis.

It was the same year that I graduated from university. There was already some pre-knowledge of what was going on. It wouldn’t be until I finished Law school in ’85 that I learnt of my own HIV diagnosis.

We probably each process the experience of being told this differently. I didn’t stop living but it certainly changed one’s perspective on life.

It was a pretty dark episode. I was just moving out into the world and as a community, we really had to shut down in terms of having haemophilia because of the enormous stigma and challenges that came with having HIV.

There are less than 1,500 of us still alive out of what was believed to be 10,000 affected by contaminated blood in the US.[ii] How I survived is probably more luck of the draw than anything else. Still, the memories haven’t gone away.

It had a heavy influence with respect to what I wanted to do, and the kinds of career choices I would make.

4) Which field of work did you end up pursuing?

![]() I did go to work in government but for the legislature – the law-making branch – which is where I got my interest in politics and policy activism.

I did go to work in government but for the legislature – the law-making branch – which is where I got my interest in politics and policy activism.

In these early days, I was chasing treatment for HIV. I wasn’t on prophylaxis yet for my haemophilia, either. It was pretty complex. I needed to relocate to a major city that had both a haemophilia treatment centre (HTC) and good care provision for those with HIV.

I ended up moving to Houston to work for an insurance trade association. In hindsight, I learned an awful lot about the mindset of insurers and payers in terms of costs and the evidence needs.

Eventually, I was promoted and found myself in the capital, Washington, DC.

5) What drew you to haemophilia advocacy?

![]() It was really the HIV crisis…

It was really the HIV crisis…

I had an interest and participated in federal advisory committee meetings. I learned the business of fractionation, pathogen risk, what went wrong, and how we could correct it.

That was probably one of my coping skills. I don’t know if I felt any anger, but I put my energy into making sure this tragedy didn’t happen again. It was also about protecting the next generation.

I got involved with the Advocacy Committee and blood safety work of the NHF.

By 1997, with 10 years of senior level experience in the state legislature, I was elected onto the NHF Board of Directors. Four years later, I became president.

6) Does anything stand out during your tenure as president of the NHF?

![]() Into the millennia, recombinant clotting factor products in the US were defined as the standard of care. They were still relatively new, largely driven by the pathogenic problems of prior treatments.

Into the millennia, recombinant clotting factor products in the US were defined as the standard of care. They were still relatively new, largely driven by the pathogenic problems of prior treatments.

One of the biggest campaigns was fighting to finally get the budget authorisation passage and funding of the Ricky Ray Relief Fund Act for contaminated blood victims.[iii]

Following this, I think another really important aspect was making sure the organisation began to turn a new leaf. I wanted to shift some of the focus and relevance to newly diagnosed families, women with bleeding disorders and other affiliated groups. They had all been incredibly supportive and loyal but had their own needs and priorities as well.

I actually think that the whole process we went through really catalysed the community to come together.

7) From one presidency to another… was the WFH always on your radar?

![]() My aspiration wasn’t to become WFH president… well, I didn’t know it was my aspiration! I still had a lingering desire to be active globally and really understand what was going on.

My aspiration wasn’t to become WFH president… well, I didn’t know it was my aspiration! I still had a lingering desire to be active globally and really understand what was going on.

Because of the blood safety work I was doing, the WFH had invited me to be part of the Global Blood Safety Advisory Committee. This was my first exposure internationally. Again, the contaminated blood issue took me there.

In 2002, I ran for a lay position on the WFH Executive Committee. I wasn’t successful as it’s quite competitive and I guess I wasn’t well known enough. But Brian O’Mahony , my predecessor as WFH president, had the courage to co-opt me onto the board a year later.

, my predecessor as WFH president, had the courage to co-opt me onto the board a year later.

Then, in 2004, I didn’t run for the board again. I ran for president.

Having experienced the full evolution of treatment, I can relate to access challenges in large parts of the world. There were a combination of things that seemed to resonate with colleagues, whereby my skillset could be transferred worldwide.

8) How did you put your stamp on the WFH?

![]() Becoming president wasn’t a matter of starting from scratch, it was about building on the extraordinary list of things Brian had achieved.

Becoming president wasn’t a matter of starting from scratch, it was about building on the extraordinary list of things Brian had achieved.

One of his flagship initiatives was the Global Alliance for Progress (GAP), launched in his last year of office. I always joke with Brian, even 15 years on, that it was like a parting gift for me!

But I think that’s the courage of a leader; to want to do something profound and actually get it going.

We really carried it forward. Keeping the GAP programme as a cornerstone, we started a new planning process. I wanted to create a global strategic vision built around a set of core themes. Then the concept of ‘Treatment for All’ was conceived.[iv]

This was and still is an incredibly lofty goal. It really means not leaving countries behind and figuring out where the development gaps are. But if we don’t have an aspiration and identifying vision, then we don’t know where we’re going. You’ve got to know where you’re going to write the roadmap to get there!

9) In your view, is Treatment for All still attainable?

![]() I am optimistic. I do think we’re making progress, as daunting as it seems. You can definitely see remarkable pockets where WFH has made an impact. It’s fair to say we are further ahead than we may think.

I am optimistic. I do think we’re making progress, as daunting as it seems. You can definitely see remarkable pockets where WFH has made an impact. It’s fair to say we are further ahead than we may think.

The challenge is keeping pace with population growth and other expansions. The purchase and production of clotting factor isn’t so fast. If you use product as the sole metric, which I would object to, then it may be less evident.

But treatment is so much more than just the product; building essential medical expertise and infrastructure is the priority. Otherwise, product, when it is available, will be misused. It’s all of the other physical aspects around living with the disease, and the organisation of care that makes a huge difference in the absence of clotting factor.

During my Presidency, we started laying the foundation for a dramatic expansion of the Humanitarian Aid Programme and added 20-plus member countries. Now the organisation covers over 95% of the world’s population. We’re making strides in diagnosing people and I’m hopeful that treatment inequality and economic barriers can be overcome.

10) Could access challenges become obsolete considering the potential of curative therapies for haemophilia on the horizon?

![]() I may be somewhat idealistic, but I actually don’t think it’s unrealistic.

I may be somewhat idealistic, but I actually don’t think it’s unrealistic.

An analogy I like to use is the telecommunications industry. Some countries without a system – instead of putting up telephone lines – have jumped straight to cell phone technology. This type of generation or technology ‘skipping’ isn’t unreasonable when considering novel innovation in haemophilia.[v]

It might not be immediate, but I am optimistic. I’d like to think the adoption of new therapies won’t trickle out globally as we’ve seen with clotting factors. These were introduced in the US some 30 to 40 years ago, yet many countries are still waiting.

There may also be a time when healthcare is delivered by way of telemedicine, rather than the traditional model of treatment centres, thus being a more cost-effective approach.

11) What’s your personal view of switching to a novel therapy?

![]() Thinking about my own situation, how do I know when to say yes to what comes next? Should I be jumping straight onto gene therapy[vi] or switching to one of the non-substitutive technologies?[vii]

Thinking about my own situation, how do I know when to say yes to what comes next? Should I be jumping straight onto gene therapy[vi] or switching to one of the non-substitutive technologies?[vii]

I do ask myself what’s most important to me: treatment burden? High level of coverage? I’m not sure there’s one right answer. The fact that treatment is personalising makes it all the more complex. Our respective choices may well be very different.

We unquestionably need lots of longitudinal data collection. I may decide that the certainty of what I can expect from a therapeutic is more important than being ‘cured.’ Then again, I might be willing to take the risk of the unknown with a gene therapy first, knowing I could fall back onto a different agent.

In any case, we mustn’t misinterpret how integral the HTCs and integrated care will be for the future. Just because we’re moving onto a novel technology, doesn’t mean the underlying issues and ‘baggage’ – be it comorbidities or joint arthropathy – will disappear when we switch. We’ll need both physiological and psychosocial support as well as learning how to live life with a mild phenotype.

These are good problems to have but we’ve got a lot to think through together.

12) How do we ensure that the most therapeutic advantageous treatments are available to us?

![]() With this technological explosion, there’s an increasing importance on value from health authorities and payers. But perhaps a lot of decisions to date have been made based on things that don’t necessarily address the most important outcomes for us as the people living with haemophilia.

With this technological explosion, there’s an increasing importance on value from health authorities and payers. But perhaps a lot of decisions to date have been made based on things that don’t necessarily address the most important outcomes for us as the people living with haemophilia.

What facets of haemophilia are there to measure, beyond just counting how many bleeds you’ve had? How you get to a zero-bleed rate matters. Annualised bleed rate (ABR) or number of bleeds per year, just doesn’t tell the whole story with the emergence of new products.

It’s our obligation as a community to tell this story. It means that we now need alternative data collection methods to complement the clinical picture, with more societal, quality of life (QoL) metrics.

This is where the Patient Reported Outcomes, Burdens and Experiences (PROBE) Study comes in…

13) Tell us more about PROBE…

![]() The PROBE study is for people living with haemophilia, directly speaking without interpretation, about what’s relevant to them. What we then try to do is aggregate and quantify their meaning.

The PROBE study is for people living with haemophilia, directly speaking without interpretation, about what’s relevant to them. What we then try to do is aggregate and quantify their meaning.

Hopefully, we can humanise what a zero ABR actually is, and how lifestyle choices align with people’s aspirations and hopes; that haemophilia fits in with whatever they want to achieve.

We’ve been collecting data globally now for four years, including the UK. As a result, we’ve developed a validated survey tool that we think captures the aforementioned.

The study’s continuing as we speak. Our idea is for patient organisations and societies to use the data to support their respective advocacy efforts and encourage decision makers to view each of us as a whole person, not just a statistic.

14) What other aspects of haemophilia care should we be focussing on right now?

![]() To me, there’s a much greater need for shared-decision making within a treatment centre process. Instead of a doctor walking in and saying, “What was your bleed rate last year?” The question should be, “What do you want to do in life? What are your career and education goals?”

To me, there’s a much greater need for shared-decision making within a treatment centre process. Instead of a doctor walking in and saying, “What was your bleed rate last year?” The question should be, “What do you want to do in life? What are your career and education goals?”

As you align the aspirations with the treatment, my gut tells me we’re going to be more compliant because we’re getting what we want… we’re going to be more engaged in our care.

There is a risk that we disengage as treatment improves; we don’t see the need for treating because we’re unaware of the consequences. I really think healthcare needs to shift to more goal-attainment focus, more personalisation. We need to be having these conversations!

15) Do you have a final message that you would like to share with the community?

![]() We’re drinking from a firehose right now! There is so much new information and lots of thought has to go into it.

We’re drinking from a firehose right now! There is so much new information and lots of thought has to go into it.

For a long while, we’ve had one type of product choice and we’ve been treated relatively uniformly. The concept of personalisation and treating the person, not haemophilia generically, is a revolution. This requires education.

It’s not just going to come from the clinicians; we all have to be educated if we’re going to match that up. I think that’s a challenge for patient societies to inform and upskill its members.

It’s also going to require change in the way care is delivered. Then we’re going to have to work with all stakeholders and say, “This is what we’ve collectively agreed on and want… what are you going to require from us to help demonstrate it?”

We really need everyone with haemophilia and other bleeding disorders to participate in research. When you’re asked to take QoL and patient outcomes surveys and report data, know that it’s for a purpose.

It’s massive re-education that has to occur across the space if we want to advance!

––– End –––

Now THAT is a call to action!

We want to say a huge thanks to Mark for featuring in the series and demonstrating the importance of meaningful patient involvement to drive haemophilia management and care forward.

If you have a question or comment for Mark about this interview or anything related, please get in touch using Facebook or Twitter with the hashtag #FactorThis. You can also leave a message below and refer to our privacy policy statement here.

On The Pulse

Notes:

[i] By 1965, Dr. Judith Graham Pool, a researcher at Stanford University, had discovered a process of freezing and thawing plasma to get a layer of factor-rich plasma, known as cryoprecipitate. Dr. Pool’s almost accidental finding was a major breakthrough in treating people with haemophilia around the world. For more information, read Judith Graham Pool and the discovery of cryoprecipitate (Kasper CK. Haemophilia 2012;18,833-835).

[ii] The first case of HIV linked to blood products in the U.S. was reported by the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in early 1982. Tragically, between 1981 to 1984, more than 50% of the haemophilia population in the U.S. had already become infected. This period is documented in the freely available editorial entitled, The tragic history of AIDS in the hemophilia population, 1982-1984 (Evatt BL. J Thromb Haemost 2006;4:2295–301).

[iii] In 1998, the US federal government set up the Ricky Ray Relief Fund Act to provide compassionate payments to individuals with haemophilia and other bleeding disorders, who contracted HIV due to contaminated clotting factor products. It was named after one of the three Ray brothers, who all lived with haemophilia and gained national media attention in 1986 when they were denied entry into their Florida school because of having HIV as a result of their treatment. The Act is available to read in full here.

[iv] Mark’s vision of treatment for all was first published in 2006 and available to access online here (Skinner MW. Haemophilia 2006;12(3),169-173).

[v] The concept of gene transfer as a key for people living with haemophilia in developing countries to also finally achieve access to care on a wide scale, is outlined by Mark in Gene Therapy for Hemophilia: Addressing the Coming Challenges of Affordibility and Accessibility (Skinner MW. Molecular Therapy 2013;21(1):1-2).

[vi] In December 2017, we reported on the landmark gene therapy studies being conducted in haemophilia. Read it here.

[vii] Novel technologies being pursed in haemophilia are summarised in the freely available editorial entitled, A golden age for Haemophilia treatment? (Makris M, et al. Haemophilia 2018;24(2),175-176).

Feature image design created by Two Cubed Creative.