This year, the Irish Haemophilia Society (IHS) are celebrating their 50th anniversary. At its helm is probably one of the most notable driving forces to have graced the global bleeding disorders community – Brian O’Mahony.

Living with haemophilia B himself, Brian’s been a staunch advocate for over 36 years of improving treatment and care. As well as steering significant action and change in Ireland, Brian made his mark on the international stage as President of the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) between 1994-2004.

In 2011, Brian became President of the European Haemophilia Consortium (EHC). Coincidentally, he had attended the very first meeting 22 years earlier, to establish collaboration amongst National Member Organisations (NMOs) across Europe.

His unwavering commitment to drive and implement new standards of care is still very much evident today.

Continuing with our Factor This! blog series, we had the privilege to hear from Brian about the impact of Ireland’s haemophilia past in setting benchmarks for care in the present, how the EHC are addressing inequality, and his treatment predictions for the foreseeable future…

blog series, we had the privilege to hear from Brian about the impact of Ireland’s haemophilia past in setting benchmarks for care in the present, how the EHC are addressing inequality, and his treatment predictions for the foreseeable future…

1) Brian, how did you first get involved with the IHS?

![]() By 1982, I was living in Dublin having just gained my masters and fellowship in biochemistry. At that time, my uncle was on the Executive Board of the IHS and persuaded me to join him.

By 1982, I was living in Dublin having just gained my masters and fellowship in biochemistry. At that time, my uncle was on the Executive Board of the IHS and persuaded me to join him.

I was young, newly married and enjoying my career. And with my science background, I decided that I wanted to give something back.

2) What was the IHS like when you joined?

![]() It was a very small organisation. There was no office or permanent staff. A group of people were doing their best to put out a few newsletters and arrange a couple of events during the year. The annual budget was only £4k!

It was a very small organisation. There was no office or permanent staff. A group of people were doing their best to put out a few newsletters and arrange a couple of events during the year. The annual budget was only £4k!

I was glad to be involved as I liked everyone. But there wasn’t a lot of activity to talk of.

Then it all changed with the contaminated blood products…

3) What do you remember from this period?

![]() Absolutely everything – my commitment increased when HIV hit the community.

Absolutely everything – my commitment increased when HIV hit the community.

I recall speaking at a board meeting in 1983 where I expressed my concerns about this ‘new’ virus. We came to learn how devastating it would be.

I became Chairman in 1987 and we made it our number one priority to help those affected. Fewer members with haemophilia B were actually exposed to contaminated product, in comparison to haemophilia A. I was very fortunate not to contract it.

However, it was difficult for those with HIV to speak publicly about it. I became their de facto spokesperson. I felt they had been badly treated by the state and somewhat abandoned.

We put together a very strong case to get the help they needed from the Irish government. I naively thought they would listen. But we were ignored!

4) How did the IHS react?

![]() That’s really when we became politically active.

That’s really when we became politically active.

We ran a very strong advocacy campaign in 1988, which actually resulted in the fall of the government in 1989 after they were defeated on a vote in parliament on this issue. That’s why haemophilia in Ireland has always been politically strong.

We did a second campaign in 1991 to get proper compensation for our members, which was successful!

5) Did the community feel they could move forward?

![]() Well, having jumped one hurdle, along came hepatitis C…

Well, having jumped one hurdle, along came hepatitis C…

We advocated for compensation for these members, too. It resulted in a compensation tribunal in 1996. Following this, there was a full statutory inquiry into the infection of people with haemophilia with HIV and Hepatitis C from 2000 to 2002.

Although an arduous process, out of this came a set of recommendations for the future.

Our point was that terrible things have happened to our community. The best way to avoid this ever occurring again is to be in the room when decisions are being made.

There’s no major initiative taken in Ireland for haemophilia without consultation with the IHS.

~

6) How did treatment change as a result of your advocacy work?

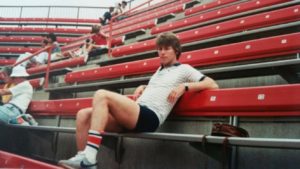

![]() As far back as 1992, we drafted a Blood Product Policy to get the safest and most effective treatment.

As far back as 1992, we drafted a Blood Product Policy to get the safest and most effective treatment.

With concern at that time around the safety of plasma-derived factor concentrates, it was of the upmost importance that we had access to recombinant clotting factor.

Before the millennia, we were probably one of the first countries in Europe to go all recombinant.

Plasma-derived products today are extremely safe and have a very good 20-year safety record. But the move to recombinant was still very important.

7) What is Ireland’s position with treatment today?

![]() I’m vice Chair of the Haemophilia Product Selection and Monitoring Advisory Board. By having an efficient process, cutting out unnecessary costs and promoting more competition, we’ve actually been able to get lower prices. In turn, this has then been reinvested in more treatment.

I’m vice Chair of the Haemophilia Product Selection and Monitoring Advisory Board. By having an efficient process, cutting out unnecessary costs and promoting more competition, we’ve actually been able to get lower prices. In turn, this has then been reinvested in more treatment.

Consequently, we’re getting more aggressive treatment regimens, and everybody is on prophylaxis.

In 2002, we were using 3.7 international units (IU) of clotting factor (F)VIII per capita, which was quite good globally at the time. Last year, we used 11 IU per capita – the highest in the world[i]! Our FIX usage of 2.6 IU per capita was also the highest.

8) Which type of products are widely used in Ireland?

![]() Our intention has always been to get the very best for the Irish community.

Our intention has always been to get the very best for the Irish community.

Therefore, in 2017, we switched everyone living with haemophilia B to extended half-life (EHL) clotting factor. We’re currently doing the same for haemophilia A.

Again, we’re the first country in the world to switch everybody to EHL products. I think it’s a milestone!

![EHL Factor Concentrates: Your Questions Answered [Video]](http://onthepulseconsultancy.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/EHL-chart-300x200.png)

[Source: Haemnet]

9) What was the main reason for switching?

![]() There’s no doubt that EHLs are more efficacious because they give you a higher clotting factor level for longer.

There’s no doubt that EHLs are more efficacious because they give you a higher clotting factor level for longer.

With both FVIII and FIX, you have the prospect of extending the time between infusions, whilst maintaining or increasing protection. That’s changing quality of life.

We’re gathering invaluable data pre- and post-switch, which should be of interest globally. After all, we’re switching an entire population in one go, not just a cohort of people.

10) How has the community reacted to the switch?

![]() Extremely positively!

Extremely positively!

You’d expect a certain level of concern or trepidation, especially from those who’ve been using the same product for years. But there’s been none of that.

This, I’m sure, is because they’ve been very well informed. Either through the IHS, their clinicians or our joint meetings before the switch.

Also, reassurance comes from a letter jointly signed by the national haemophilia director and myself. So, they’re getting a collaborative view from the clinicians and the IHS, which I think is really important.

11) Which other approaches have you adopted in Ireland?

![]() We’re clearly now in the era of personalised care. The days of standardised prophylaxis are gone.

We’re clearly now in the era of personalised care. The days of standardised prophylaxis are gone.

So much about the individual is taken into account when deciding their treatment regime. You should be able to walk into a clinic and have your clotting factor tailored based on aspects like your previous bleed history, lifestyle and aspirations.

Up to now, it’s been more of an art than a science. Now there’s the ability to capture and apply this information and data.

~

12) Thinking about wider Europe… what is your overall perspective on the current situation?

![]() With my EHC hat on, there’s clearly been an improvement in haemophilia care across the continent.

With my EHC hat on, there’s clearly been an improvement in haemophilia care across the continent.

Over the last nine years, we’ve conducted a detailed survey on every aspect of care. We’re seeing more prophylaxis for adults, generally more use of clotting factor as well as gaps in comprehensive care being filled.

You know, we haven’t been surveying just for the sake of it; it’s about getting a real picture of what the needs are. As a result, our recommendations have been the basis for many recommendations endorsed by both the European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines (EDQM) and subsequently, the Council of Europe(CoE).

This gives a strong base for advocacy by all of our NMOs to go to their governments and hold them accountable. It’s really key!

13) How else are the EHC working to reduce disparities?

![]() In Western Europe, we’re talking about very exciting developments; other EHLs, novel therapies and being on the cusp of gene therapy. Yet, some countries in central and eastern Europe are stuck in a morass of having distinctly low clotting factor use.

In Western Europe, we’re talking about very exciting developments; other EHLs, novel therapies and being on the cusp of gene therapy. Yet, some countries in central and eastern Europe are stuck in a morass of having distinctly low clotting factor use.

We’ve identified 14 countries below the CoE minimum standard. One of the problems we face in the market place is with reference pricing; if an emerging country is offered lower prices for clotting factor, then developed wealthy countries will want the same. This has led to a reluctance by pharmaceutical companies to offer real value to these countries.

What’s more, their governments do one-year budgets, which can often lead to a shortage of clotting factor.

Hence, we launched the Procurement of Affordable Replacement Therapies – Network of European Relevant Stakeholders (PARTNERS) programme!

14) Tell us more about PARTNERS…

For two years since we started this initiative, we’ve been going into these countries and forensically examining every element of their haemophilia care and procurement process.

We talk to their health ministries, doctors and haemophilia organisation. By extending the funding for national tenders to three years, product can be made available below a ceiling price.

We’re in the process of having these conversations and pushing people towards change that’s needed, and it’s going on a pace. Of course, you hear things like, “We can’t do that, we’ve always done it this way…” That’s not an acceptable answer!

By its very existence, PARTNERS is having an organic effect amongst these nations and neighbouring states and assisting them in optimising their supply of affordable factor.

15? How do you see the shape of haemophilia now and in the future?

We’re certainly going to see more progress in haemophilia therapy in the next five years than the last 25!

EHLs and novel therapies are increasing competition with standard clotting factor, which may have to find new markets globally at competitive rates. One of my hopes is that we start to see more availability of treatment right across the spectrum, not just for the wealthy countries.

In many places, for example western Europe, together with an increased use of EHLs, we’ll start to see more subcutaneous therapies for both inhibitor and non-inhibitor patients. This will require continued and additional comprehensive care, as they’ll necessitate a change in mind-set amongst clinicians and the community in terms of the way they’re used.

Then, of course, gene therapy is only a couple of years away. We’re going to see a big debate, not just about its concept but the economics; how and when will it be made available, who will have access to it, what will it cost and how will we pay for it?

I’m looking forward to seeing how it all unfolds. How about you give me a call back in 2023 and we can see what progress we’ve made…

—

We’ll hold you to this, Brian!

We want to say a big thank you to Brian for taking the time to chat to us and for his outstanding service to the whole community.

Brian was quick to acknowledge the hard work and dedication from all of the staff and volunteers at the IHS and EHC for the successes to date.

Now, we would like to hear from YOU! What would you like to see happen for haemophilia over the next five years? Let us know on Facebook or Twitter using the hashtag #FactorThis.

See you next time,

On The Pulse

Notes:

[i] The WFH has established that one IU of FVIII per capita should be the target minimum for countries wishing to achieve survival for the haemophilia population. Higher levels would be required to preserve joint function or achieve a quality of life equivalent to an individual without haemophilia. [Source: WFH Annual Global Survey 2016]

Feature image design created by Two Cubed Creative.